Towards Super-Human Data Intelligence

We discuss state of the art performance on an AI benchmark.

TL;DR: What We Found

1. LLM-Based SQL generation isn’t enough: Simply prompting a language model to “write SQL” produces brittle, inconsistent results. Even strong models fail on schema ambiguities, incomplete metadata, and subtle logical requirements.

2. Our approach involves a deliberative, metadata-aware Agentic pipeline that performs dramatically better. Our system breaks the task into a series of steps involving:

a. Query planning

b. Structured reasoning over schema and semantics

c. Validation and critique using model-driven checks

d. Iterative refinement and self-improvement

Crucially, we enrich the Agent context with real metadata — carefully extracted schema details, constraints, column semantics, and sample distributions — resulting in more accurate and interpretable SQL.

3. This approach achieves state-of-the-art performance on BIRD-SQL, demonstrating the value of systematic planning and reasoning, metadata interrogation, and iterative refinement.

4. However, benchmarks are only the beginning. Benchmarks like BIRD-SQL or Spider-2 are helpful milestones, but they are not necessarily representative of messy, sprawling enterprise databases. Real-world BI systems require far more than SQL fluency: they require business context, semantic understanding, judgment, and robust error-handling.

AI that understands data is useful.

AI that understands data and business is transformative.

And now the details for the Deep-Techies…

It won’t be long before much of the information technology in the enterprise is generated and maintained by artificial intelligence. A necessary step in that direction is AI which is super-human in its ability to understand databases, especially SQL. Thus, benchmarks like BIRD-SQL are important. The focal task in this benchmark is to answer questions by generating SQL queries against a variety of databases. The databases themselves do not have as many tables or rows as enterprise databases, so leadership on the benchmark does not imply that an AI is a sufficient foundation for automating enterprise IT. Nonetheless, super-human performance on the likes of BIRD is a necessary condition for AI that can automate enterprise IT.

Within the larger ambition to automate enterprise IT is supporting so-called “business intelligence”. BI addresses such tasks as reporting on operations, such as by monitoring key performance indicators and presenting dashboards, as well as deriving informative insights. BI is extremely important to upper management. This is evident in the size of the present BI market which has yet to be substantially impacted by AI. Estimates for the size of the BI market vary from $40-70+B with ~10% CAGR, which is likely to accelerate dramatically as vendors and enterprises adopt AI.

Drilling Down into Talking to Data

One requirement for accelerating BI with AI is super-human performance on the “talk to data” task (aka TTD). Put simply, TTD enables people unfamiliar with database details to query in natural language. TTD is necessary for AI BI but not sufficient. The AI must also understand the operations of the enterprise as well as its strategies and the challenges it faces, otherwise it will not understand, for example, key performance indicators and how to derive those which are latent in data. Deriving KPIs from data involves various capabilities beyond simply talking to data, such as data analytics. Perhaps most promisingly, AI can apply capabilities such as data science to formulate predictive analytics and derive insights which are critical for improving enterprise performance.

But AI data analytics and science require the understanding and flexible access to data in TTD. Thus, again, TTD is a necessary (but not sufficient) condition for AI BI. So, let’s talk about where AI stands on TTD in the context of the BIRD-SQL benchmark...

BIRD SQL

First, let’s take a look at an example question, the SQL the dataset provides, and the results from executing that SQL on the database populated with the data provided in the dataset:

- What is the ratio of customers who pay in EUR against customers who pay in CZK?

- SELECT CAST(SUM(CASE WHEN Currency = 'EUR' THEN 1 ELSE 0 END) AS REAL) / NULLIF(SUM(CASE WHEN Currency = 'CZK' THEN 1 ELSE 0 END), 0) FROM customers

- 0.06572769953051644

In the case of BIRD-SQL, so-called “evidence” is provided for almost every dataset item. For this example item, the given “evidence” is:

- ratio of customers who pay in EUR against customers who pay in CZK = count(Currency = 'EUR') / count(Currency = 'CZK').

In my opinion, most of the evidence is self-evident (and at times misleading), especially if you’ve interrogated the database and understand the characteristics and distributions of column values.

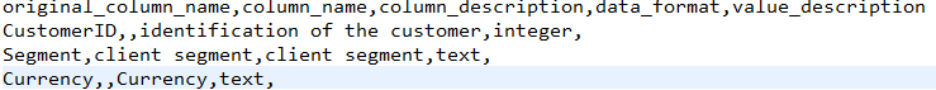

This example asks the question of the ‘debit_card_specializing’ database. For each database in the dataset there is a CSV file which provides a high-level type for the column and an optional, brief text description, such as this for the ‘customers’ table referenced in the above SQL:

Presumably, ‘CustomerID’ is the primary key for this table, but that information is not provided in the dataset.

Database Interrogation

Whether or not the benchmark provides such information, in practice, an AI will access the metadata in the SQL database itself (e.g., the data definition language or schema) to obtain more precise information about column data types, widths, nulls, foreign keys, etc. along with information about constraints and indices on tables. The benchmark does provide SQL scripts to create, alter, and populate these databases from which such information can be obtained. We did not use them. We favor direct interrogation of databases to obtain metadata such as table, column, index, and constraint definitions.

We go directly to the database to obtain metadata for table, column, and other details, such as` primary and foreign keys and constraints. We further interrogate databases for metadata not available in SQL scripts or DDL. For example, we obtain (whether exactly or approximately by sampling) the numbers of rows per table, the cardinality of relationships among table (e.g., joins), the characteristics and distributions of values in columns, etc.

Given the $ value of super-human TTD to an enterprise can easily be measured in 7 to 10 figures, it is practical to help the AI understand even more about the data as well as the enterprise by performing “deep research”, potentially including humans in the loop (HITL). When working in an enterprise context, such research includes documentation about the enterprise and its information technology, such as requirements and design documents.

Our work involving the BIRD benchmark did not involve any HITL. Our approach to “deep research” yielded sufficient rich knowledge about the databases and their domains that the BIRD provided database descriptions were not helpful. Finally, BIRD did not provide, and we did not augment it with documents describing the domain or the utility of any of the databases. Thus, our approach to BIRD is 100% automatic: connect to the databases, let the AI acquire metadata and knowledge, and evaluate on the benchmark.

Metadata Enrichment

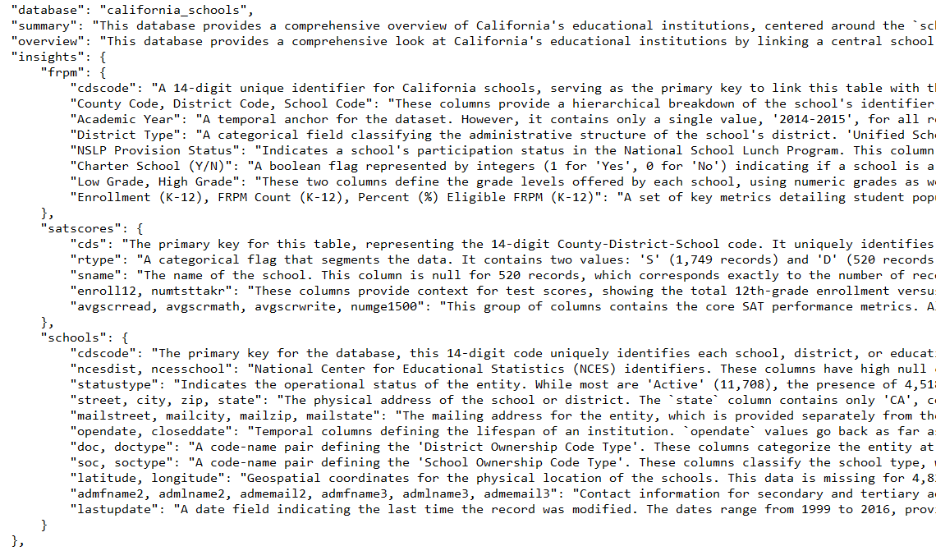

The databases in BIRD are familiar to general-purpose foundation models (GFMs) such as those from Google, Open AI, etc. Thus, the trivial column descriptions provided in the dataset were of little or no value. The naming and type information provided was also not informative beyond the metadata automatically extracted from the databases. Feeding the extracted metadata and information obtained by interrogation of the databases to GFMs prompted in various manners produces semantic descriptions:

In the enterprise setting, this enrichment is enhanced by whatever internal documents and diagrams may exist concerning existing databases or databases generated by AI from other information, such as documents about the industry or business processes of an enterprise. To keep things focused here, I’ll defer further discussion of such knowledge augmentation and its use beyond TTD, as such do not pertain to BIRD.

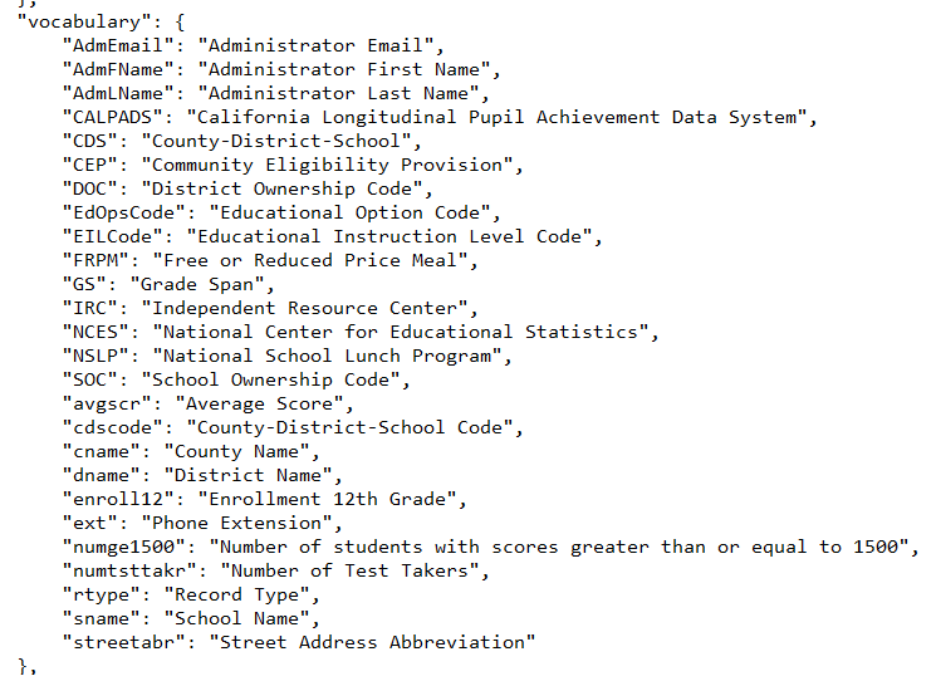

To help AI with questions that use acronyms, jargon, etc., we also obtain vocabulary, such as follows:

In addition to the foregoing, we identify entities and relationships between them and how they are represented in the data.

A Deliberative Approach

After extracting and eliciting domain and database knowledge and metadata, we proceed roughly as follows:

1. Generate satisfactory SQL given a question against a database, its “evidence”, and the enriched metadata concerning the database and an initially empty critique:

a. generate a natural language query plan

b. generate SQL and rationales using some GFM(s)

c. critique the plan, SQL, and rationales using some GFM(s)

d. amend the critique and repeat if the SQL is not satisfactory within limits

2. Get a result set or exception by executing the generated SQL against the database.

a. amend the critique and repeat SQL generation if an exception arises

3. Compare the results of the generated SQL with those from the SQL provided in the dataset item.

SQL is deemed satisfactory if there is no materially negative critique, including reaching a limit of effort or diminishing returns on improvement. In the event of failure, we use some GFM(s) to analyze the failure in a variety of ways and aggregate such analyses in the use of GFMs to revise the prompts used in planning, generating, critiquing, and analyzing. This has proven particularly effective in quickly (if asymptotically) eliminating SQL exceptions, for example.

Baseline results using thinking GFMs (including those shown on the leaderboard and our internal evaluations with more recent thinking models) indicate the need for a structured pipeline (or chain of thought) as shown in step 1. Such baseline results amount to reducing the pipeline to only the first part of step 1(b). That is, given only information about a database and a question, TTD performance is unacceptable. Performance was better with our enriched knowledge and metadata, but significantly worse than step 1 alone above achieved in our evaluations. Perhaps future thinking models will not benefit from including domain and database knowledge or metadata in context nor guidance along a chain of thought, that’s not where things stand. That’s my take but we’ll come back to this shortly below…

Evaluation Issues

BIRD evaluates results using exact match. This leads to a significant number of misleading false negative results. For example, if generated SQL uses a different precision to compute a total or average than the SQL provided by the dataset, the result will be unfairly graded as incorrect. Similarly, if the query does not specify the order in which columns should occur in the result set, an equivalent result set will be graded as incorrect. In some cases, the order of rows in the result set were unspecified also resulting in unfair grading as incorrect.

Some other SQL benchmarks address some of these limitations. To avoid grading column order differences as incorrect, one provides result sets as tables with column names as headers.

In our evaluations we addressed some but not all of the exact match issues by using a simple notion of set equivalence where 2 result set rows were deemed equivalent if they were set equal where two numbers were deemed equal if within a small fraction of 1 percent.

State of the Art Results?

Using this approach, we obtained results in-line with the state of the art, assuming the “mini” subset of the development set (500 items) are representative of the “dev” results reported on the BIRD-SQL database. Essentially, our “dev” results are approximately 75%. I believe these results may actually be better than those reported on the leaderboards, as discussed below (and elsewhere referenced below).

Deceiving Baselines

Along the way to the deliberative approach described above, we established our baseline using only basic metadata in an approach which relied on the “innate reasoning” capabilities of “thinking” GFMs. This approach was “straight thru” in that it involved no critique or iterative refinement.

This basic approach produced comparable numbers of apparently correct results versus the more sophisticated approach above. This led to speculation that GFMs already think well enough with sufficient knowledge of SQL to address TTD “out of the box”. Further investigation indicated such is not the case.

- Approximately 10% of baseline cases fortuitously” agreed with the dataset..

Here, a “fortuitous” agreement includes agreement with an incorrect result in the dataset (i.e., an actual mistake) or happening to interpret a materially ambiguous query as interpreted In the dataset (i.e., luck) or happening to produce results in the same order as in the dataset where such order cannot be discerned from the query (i.e., more luck).

- Thus, if we posted our baseline results, our entry would be near the top of the leaderboard, along with others which may be inflated by as much as 10%

This has several corollaries. First, the leaderboard is noisy. To the extent that entries agree “fortuitously”, their apparent relative performance is not informative and may be misleading. Second, striving to claim SOTA is a fool’s errand unless and until the dataset is improved.

A Dataset Inconsistency

Consider the following case, for example:

- How many percent of LAM customer consumed more than 46.73?

The “evidence” given (which I find inappropriately specific to this case) is as follows:

- Percentage of LAM customer consumed more than 46.73 = (Total no. of LAM customers who consumed more than 46.73 / Total no. of LAM customers) * 100.

The SQL given to obtain the expected answer is:

- SELECT CAST(SUM(CASE WHEN T2.Consumption > 46.73 THEN 1 ELSE 0 END) AS REAL) * 100 / NULLIF(COUNT(T1.CustomerID), 0) FROM customers AS T1 INNER JOIN yearmonth AS T2 ON T1.CustomerID = T2.CustomerID WHERE T1.Segment = 'LAM'

Executing this SQL results in 98.5267932135058.

The deliberative pipeline with critique produced the following SQL and a different result, as follows:

- WITH customer_total_consumption AS ( SELECT T1.customerid, COALESCE(SUM(T2.consumption), 0) AS total_consumption FROM customers AS T1 LEFT JOIN yearmonth AS T2 ON T1.customerid = T2.customerid WHERE T1.segment = 'LAM' GROUP BY T1.customerid ) SELECT CAST(COUNT(CASE WHEN total_consumption > 46.73 THEN 1 END) AS REAL) * 100 / COUNT(*) FROM customer_total_consumption;

- 98.38709677419355

The failure analysis at the conclusion of the “thoughtful” pipeline produces a number of artifacts, including the following in this case:

- The model correctly calculated the percentage of unique LAM customers based on their total consumption, whereas the expected SQL incorrectly calculated the percentage of monthly consumption records, leading to a different result.

On the other hand, the less deliberative approach produced a result which agreed with the dataset. That is, it was incorrectly given credit.

Saturation with Unintended Exaggeration

For another perspective, see this examination which summarizes a variety of issues with the dataset. They took a close look at 186 items in the dataset and found:

- 39 had “gold SQL statements” which were erroneous

- 57 had “noisy questions” (e.g., were unclear or ambiguous)

In total, they identified 107 of the 186 had issues ranging from serious matters above to minor issues such as spelling or syntactic errors or, in some cases, simply not being able to be answered given the database they target.

Some of these are not issues in practice. For example, GFMs perform remarkably well in the face of (minor) spelling mistakes, case variations, or grammatical errors. Failure analysis of the “mini” development dataset “found” 133 of 500 items to be deficient. This appears to be consistent with the above, realizing that we analyzed more items over 11 databases.

- Excluding such dataset inconsistencies, our deliberative pipeline achieves 100% accuracy.

Such dataset inconsistencies imply that the best results for a TTYD system on BIRD-SQL would be below 80%, which is consistent with what is being reported on the leaderboard. But caution is warranted, since the simpler “baseline” approach discussed achieved the same level of apparent performance before closer inspection. Thus, I suspect that some, perhaps many, of the results reported on the leaderboard are overstated.

More SQL Challenges

In real life, such as in an enterprise, our hands are not tied behind our backs by a benchmark’s constraints and evaluation process. Benchmarks will not be able to measure the real impact of TTD pipelines which should have HITL. The HITL can resolve the ambiguity of queries (which BIRD demonstrates are prevalent), which is unavoidable in TTD. The HITL can also directly inform TTD about misinterpretations thereby continuously improving the performance of a TTD system in specific contexts. Nonetheless, benchmarks help lift our game, so we’ll be posting again soon on another benchmark which involves much more complex databases and queries.

More From the Journal

The Validation Imperative in Agentic Science

Deriving High Quality Domain Insights via Data Intelligence Agents